Computers...in space!

I admittedly have a problem—I love, love, love space. I spend too much time geeking out on all the space missions, new and old alike. While humans still go to space and we dream of going back to the moon and beyond to Mars, a lot of that hope is probably misplaced because we simply aren’t adapted to space.

As unromantic as it is, probes and robots do a much better job of exploring space. And in order to do so, they need computers.

After 65+ years of space exploration something truly exciting is happening out there. Space tech is finally becoming more like tech on Earth. And no, it’s not all Elon’s fault. It’s also NASA’s.

Read on to learn the story of how the 4 pound “little helicopter that could” has more compute than all other space missions combined.

Analog beginnings

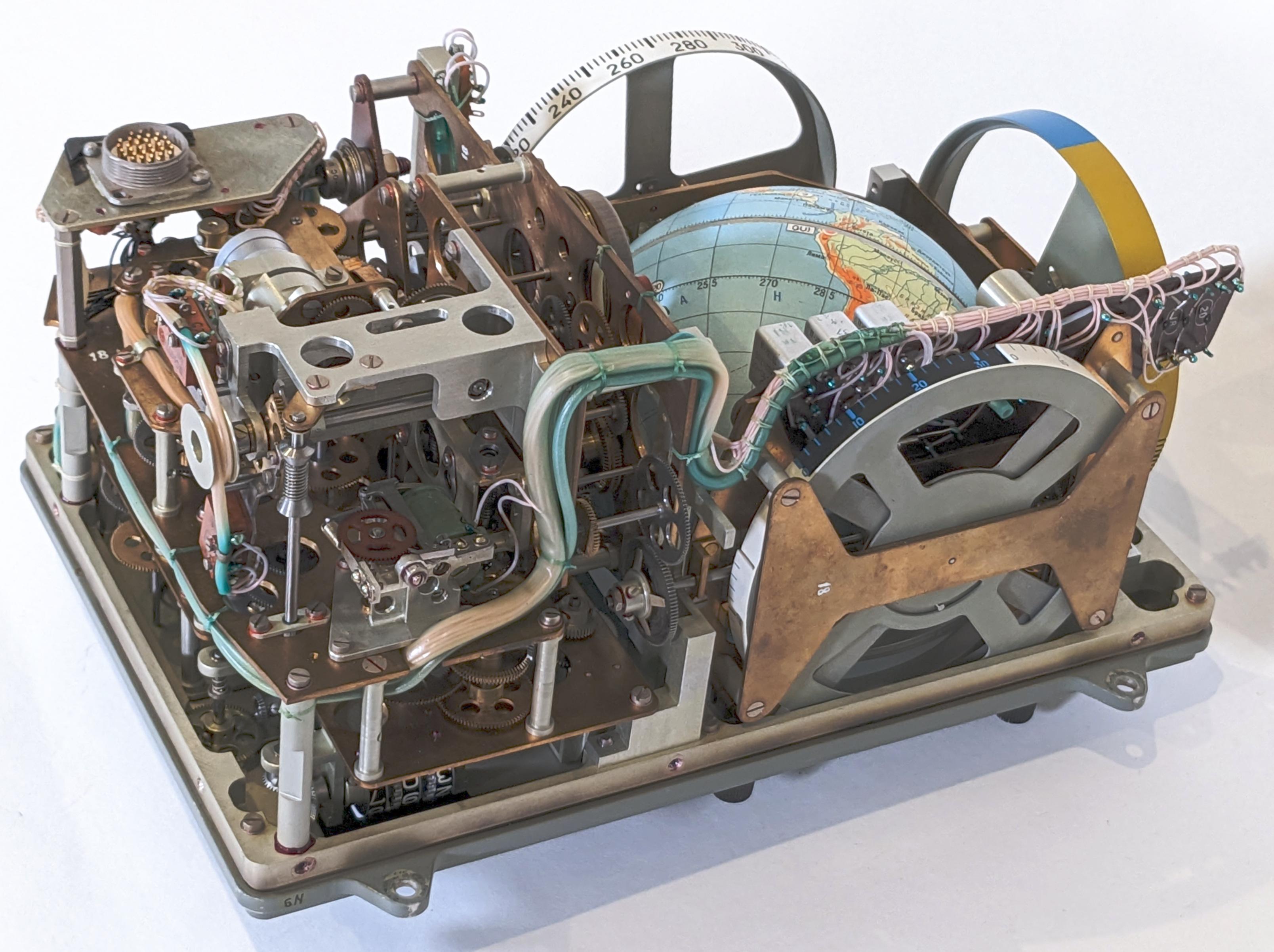

When Yuri Gagarin went to space in 1961, the Russians didn’t trust computers. Well, to be more precise, they didn’t trust electronic computers. Instead they insisted on using mechanical ones like the impressive Globus, which was more in the vein of clocks than computers, that told the cosmonauts where they were in orbit.

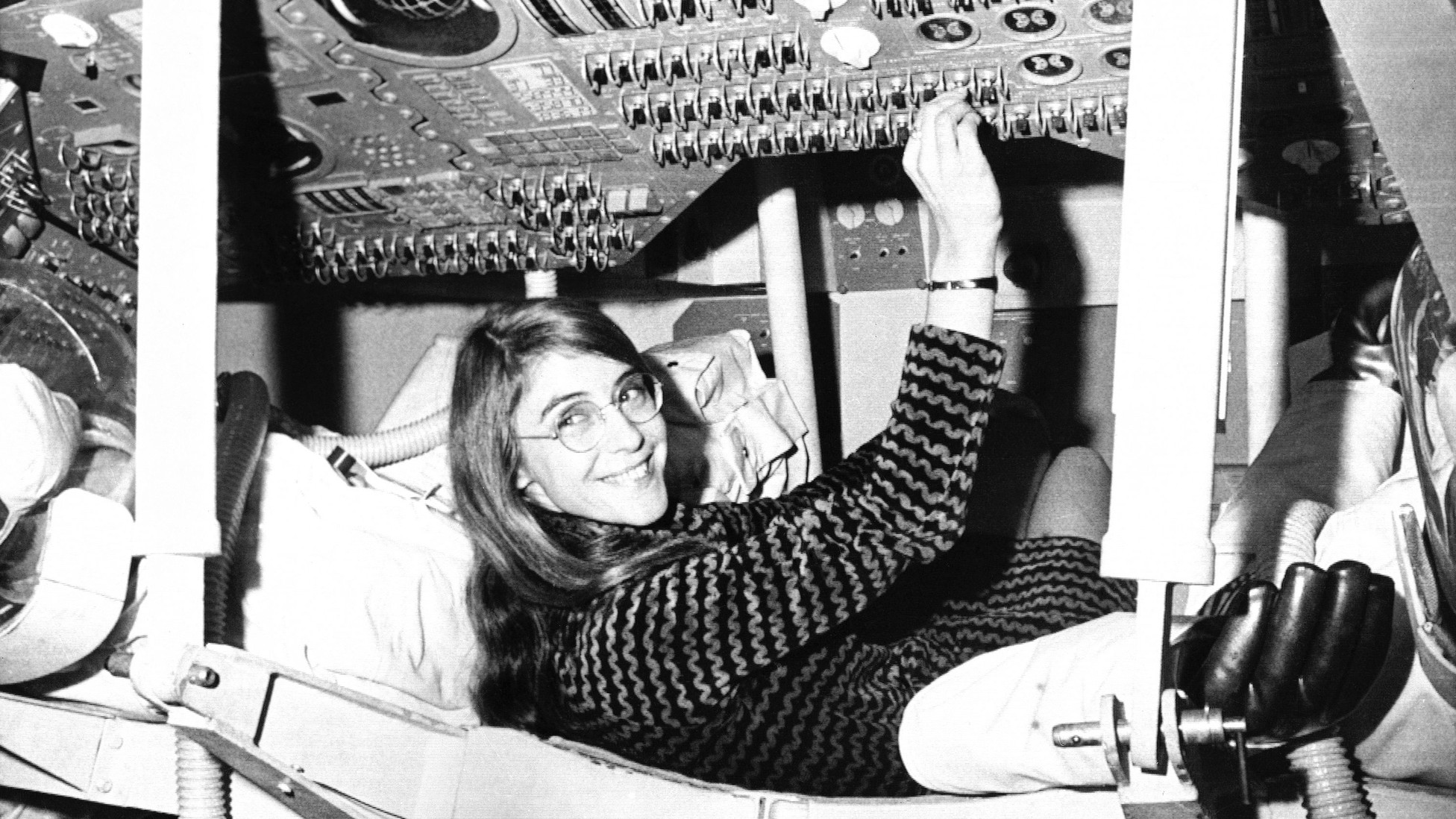

Three weeks later Alan Shepard went up to space in the Freedom 7 and he, too, didn’t have an on-board digital computer. Famously the ‘human computer’ Katherine Johnson, among many others that were featured in Hidden Figures, did the trajectory analysis of that flight. By hand.

Basically it was a guy strapped onto a missile. Clearly, though, that wasn’t going to work for getting us to the moon. We needed active guidance!

Apollo advancements

When JFK said “We’re going to the moon!!” he had no idea how exactly that would happen. Neither did many of the engineers working on Apollo.

But they eventually decided to use state of the art technology in the integrated circuit to help with the guidance system—source code here. That was a huge, albeit highly calculated, bet. Computers at the time were too bulky and heavy to make the 250,000 mile journey to the moon.

A pilot could never have navigated the way to the moon, as if a spaceship were simply a more powerful airplane. The calculations required to make in-flight adjustments and the complexity of the thrust controls outstripped human capacities.

If we were to go to the moon by the end of the decade, it had to be with integrated circuits.

Move slow and don’t break anything

After that moonshot—get it?—the tide turned once more back to risk aversion in a serious way.

The Space Shuttle had a handful of radiation-hardened (rad-hard) IBM computers that weren’t too performant but boy were they reliable and redundant. Radiation is a problem for computers in space because it can change 0s to 1s and vice versa. Typical rad-hard computers are a generation or two behind when it comes to specs, but they can withstand a million times the fatal dose of radiation for humans.

There were 4 of the same computers with the exact same software that called the shots by voting. If for any reason the 4 computers weren’t working, there was a separate fifth computer to take the helm.

The computers ran on a more or less proprietary programming language, HAL/S, and not a lot of change happened for three decades. That was kinda the whole point. In a codebase with 420,000 lines of code, there was a single error. Yes, you read that right.

“Houston, we have a problem,” may make for a good movie; it’s no way to write software.

NASA loves relying on old, expensive software with in-house code because it is safe for mission-critical systems. Think of NASA as the anti-Silicon Valley. The shuttle group even had a slogan, very much their own:

The sooner you fall behind, the more time you will have to catch up.

The rad-hard king

As more and more missions gained funding in the new millennium, a fresh rad-hard computer came on the market that could handle the harsh environment of space and protect probes from having their bits flipped.

Say hello to the RAD750, the poster child for bureaucratic space development.

Rad-hard components are spendy, heavy, and outdated. The RAD750 weighs anywhere from 500 to 1500 grams depending on the model. It also costs about $300,000. And then, in terms of performance, it’s like having some hardware from a 90s laptop. Yikes.

Still, the RAD750 can be found on popular and important missions spanning two decades:

- Deep Impact

- Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Kepler space telescope

- Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

- Juno spacecraft

- Curiosity rover

- InSight

- Perseverance rover

- James Webb Space Telescope

Ingenuity

If there had been no iPhone, there would have been no Ingenuity

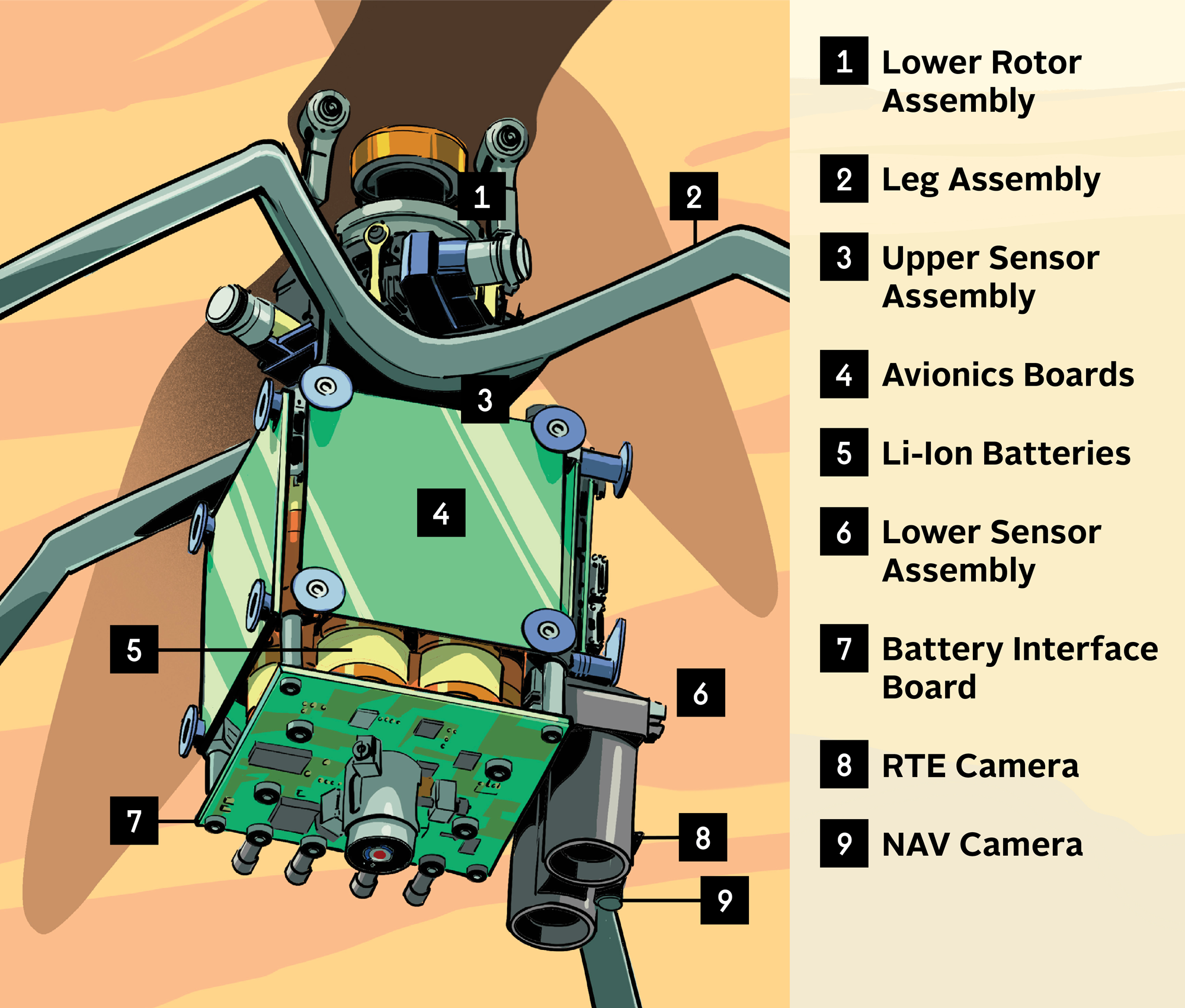

When engineers at JPL had the idea to send a drone to Mars, they faced some pretty extreme design constraints. Mars’ atmosphere is less than 1% that of Earth’s, or put another way, being on Mars is like being at 100,000 feet. The standard approach of throwing a RAD750 on a helicopter would not work because it would be way too heavy.

The team was constrained to a mass of just 4 pounds (less than 2 kg) for the entire helicopter. That is the equivalent of approximately five cans of Campbell’s soup. Those five cans of soup include your helicopter blades, which are several feet long, the batteries, the computer, the sensors and camera, the legs, the solar panel—all of it.

It seemed like the NASA thing to do would prevail and they’d spend hundreds of millions of dollars designing super specific systems for the helicopter or it’d just as soon be cancelled.

But then the unthinkable happened. The Ingenuity team decided to go shopping at Best Buy and picked up a couple cameras, a mobile phone, a smartwatch, a pair of antennas, and some batteries. That’s not how NASA usually rolls!

Ingenuity’s fuselage is even completely made out of the avionics boards filled with other parts due to weight limitations and heating requirements!

Dare mighty things

The most amazing thing is that it worked. Everything worked, and it worked rather well given the extreme conditions.

Originally designed for 1-5 flights, Ingenuity flew a total of 72 times. In just over 3 years it flew for more than 2 hours and covered some 17 kilometers.

Many people were involved, from the dozens of people at JPL to the about 12,000 developers who now have a Mars 2020 Helicopter Mission badge for their work on various aspects of the code involved. It’s worth mentioning, too, that another atypical approach for this mission—which has also seen great success—was open sourcing F`, the flight systems framework used by many CubeSats.

So, here’s a recap of the commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) approach:

- Cut costs considerably

- Made development easier and faster

- Saved weight and volume

- Increased compute by an order of magnitude

And it might just make exploring space a little more exciting.