Getting to blinky

Starting small but starting

I think it’d be pretty rad to be involved in software for space exploration and the burgeoning space economy. However, I know nothing about embedded systems.

Fortunately there’s no better time than the present for getting into embedded. Hardware is cheap and resources are plentiful.

Really there’s no excuse to get started, especially for someone who has only a few responsibilities like keeping the cats fat and happy and the dog active.

My kit

After very little research, I bought a Kepler Kit because it had a bunch of trinkets that looked fun to play with. It’s probably nearly identical to any starter kit and includes:

- a Raspberry Pi Pico W

- a breadboard

- LEDs

- resistors

- motors

- speakers

- displays

- buttons

The kit says it’s for use with MicroPython or C, but I don’t foresee Project Kuiper hiring MicroPython devs. I’ll be programming in Rust.

Delays

I didn’t get to fiddle around with my kit before leaving for spring break, so I brought it with me on the road. Trouble was I didn’t have the USB-C to USB adapter needed to work with the Pico from my Macbook.

Long story short, I ended up getting an adapter at the Best Buy in Bellevue and squatting in the Microsoft Visitor Center for an hour while I figured out the basics to get to blinky, essentially the embedded equivalent of “Hello, World!”

Luckily it was pretty simple! Turns out that using crates like embassy is extremely helpful and powerful. I wrapped up with two hours to spare before heading to the Seattle Rust User Group at the Reactor on East Campus across SR 520.

The code

//! This example toggles RP Pico/W GPIO pin 0

// connect a resistor and LED and it will blink.

#![no_std]

#![no_main]

use defmt::*;

use embassy_executor::Spawner;

use embassy_rp::gpio;

use embassy_time::Timer;

use gpio::{Level, Output};

use {defmt_rtt as _, panic_probe as _};

#[embassy_executor::main]

async fn main(_spawner: Spawner) {

let p = embassy_rp::init(Default::default());

// Configure GPIO pin 0 as an output

let mut led = Output::new(p.PIN_0, Level::Low);

// Loop forever

loop {

// Light up the LED

led.set_high();

// Wait for 1 second

Timer::after_secs(1).await;

// Turn off the LED

led.set_low();

// Wait for 1 second

Timer::after_secs(1).await;

}

}Breaking it down

In the simplest terms, all that is going on is we’re oscillating between high and low voltage at one pin that’s connected to an LED, turning it on and off.

But there’s actually much more to it than that.

#![no_std]

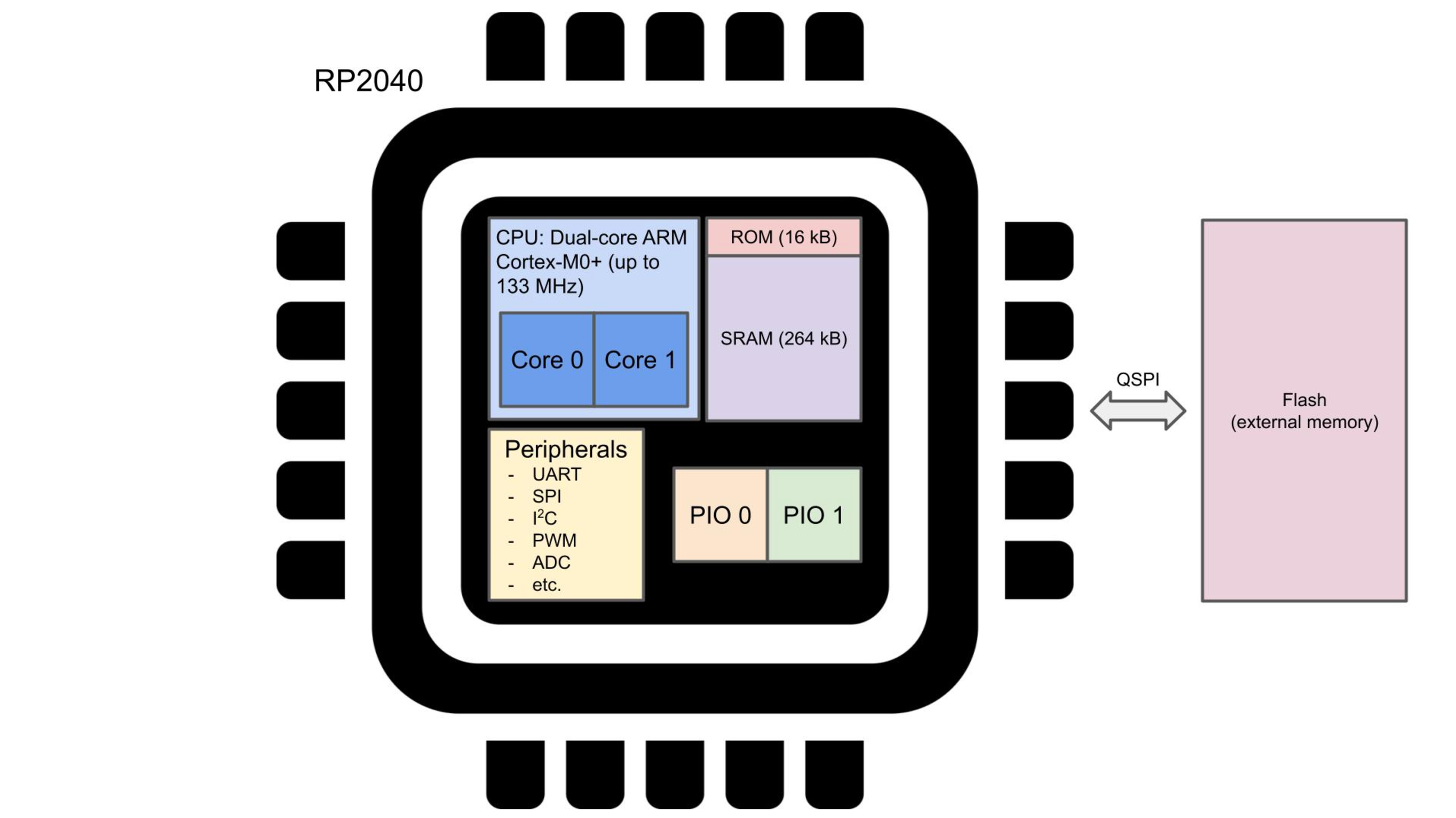

#![no_main]Looking at the code, we aren’t using either the standard library or a main function. This is pretty common for embedded or bare metal programming because it eliminates all the fluff and stuff. Every bit counts when it comes to microcontrollers.

use embassy_executor::Spawner;

use embassy_rp::gpio;

use embassy_time::Timer;

use gpio::{Level, Output};We’re also leaning heavily on embassy, which is an EMBedded ASYnc crate with “time that just works.”

Rust has async functionality built-in with Futures but oddly enough does not come with its own async runtime like JavaScript or C#. There are plenty of options out there to choose from, like Tokio or Monoio, but here embassy makes the most sense.

In short, the executor is the async runtime, allowing us to use a timer to turn the LED on and off again, forever.

The embassy_rp::gpio::Output::new() method allows us to create a pin with an initial output level which we’ll set to low, or off. For this we’re using pin 0, so we also have to make sure that our circuit ties into that slot on the breadboard or nothing will happen.

Side note: it’s also best to have a resistor before the LED to cut the 5 volts coming off the Pico so as not to fry the LED. Or something.

Then the embassy_time::Timer::after_secs() makes it a breeze to wait for however long before moving on to execute the next line of code. Here it’s just 1 second.

use defmt::*;defmt is pretty dope! In this example it’s not really used much, but the idea is brilliant and is best summarized by quoting the book:

Deferred formatting means that formatting is not done on the machine that’s logging data but on a second machine. That is, instead of formatting 255u8 into “255” and sending the string, the single-byte binary data is sent to a second machine, the host, and the formatting happens there.

MEMORY {

BOOT2 : ORIGIN = 0x10000000, LENGTH = 0x100

FLASH : ORIGIN = 0x10000100, LENGTH = 2048K - 0x100

RAM : ORIGIN = 0x20000000, LENGTH = 264K

}Then there’s the memory.x file that declares the memory addresses of key components like second stage bootloader, flash, and RAM. The addresses are in hexadecimal—aka base-16—since it’s a more compact and concise way of representing large numbers. The memory address for where the RAM starts is 0x20000000, or 536,870,912 in base-10.

It’s also worth mentioning the config.toml, in the hidden cargo folder, which looks like this:

[target.'cfg(all(target_arch = "arm", target_os = "none"))']

#runner = "probe-rs run --chip RP2040"

runner = "elf2uf2-rs -ds target/thumbv6m-none-eabi/debug/blinky"

[build]

target = "thumbv6m-none-eabi" # Cortex-M0 and Cortex-M0+

[env]

DEFMT_LOG = "debug"All this code does is make sure that the target is correct—thumbv6m-none-eabi for Cortex-M0/+—and that the runner gets the binary in the right format. Here it’s going from ELF to UF2 in Rust via elf2uf2-rs. The -ds flag gives us automatic deployment to a mounted pico in addition to opening the pico as a serial device and printing serial output.

The last thing to do is to hold down the button on the Pico when plugging it in via USB so that when we execute “cargo run” via the terminal all the code is cross compiled and loaded on to the Pico. It’ll then run the code without an operating system and that’s pretty sweet!

Wrapping it up

But why did I go with a blue LED? I’m glad you asked.

Veritasium has a very detailed answer. The gist of it is it was really hard to make blue LEDs and thus complete the RGB trio needed to make white light or any and all colors. The guy who invented them won a Nobel Prize for it.

Kind of a big deal.

Check engine

In a weird way, this basic exercise gave me the confidence to investigate my check engine light that’s kept popping up over the past half year. I looked at the codes—349 and 394—and learned that the camshaft sensors were misbehaving.

One possible problem was a faulty connection in the wiring, and that’d be nice because then I wouldn’t have to pay for a more thorough investigation or bigger fix.

So I popped the hood, took off the connectors for both the A and B banks, then tested all 3 pins with a voltmeter to see if they were reading 5 V, just like the Pico uses.

Sadly they all were sitting squarely at 5 V, meaning it’s not just the wiring. Guess I’ll have to go into the shop one more time.